Ancona Robin John and Little Ephraim Robin John late 18th c. — ?

The transatlantic slave trade was driven by the European demand for laborers and the willingness of some African leaders and merchants to provide a supply of captives in exchange for European goods. Some of the Efik people of Old Calabar (Nigeria) were among those willing to trade with Europeans. The story of Grandy King George, his brother, Little Ephraim Robin John, and nephew, Ancona Robin John provides insight into the complexity of individuals’ experiences in an Atlantic world shaped by slavery. The Robin John family were slave traders in the Bight of Biafra.

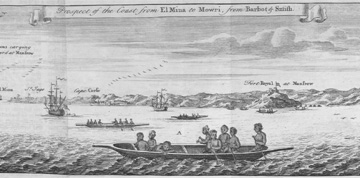

Grandy King George established trade relations with ship captains and merchants in Bristol and Liverpool, England. He wrote letters to record personal and business transactions with his business partner in Bristol, Thomas Jones. Once the British slave-ship captains arrived in Old Calabar, the negotiations began. Once satisfied with the exchange agreement, Grandy King George would send his men in large canoes to wage war and capture Ibo and Ibibio speaking people for captives.

The slave-trading business depended on a level of trust among traders, which meant that relationships were often fragile. In 1767, trade negotiations between King George and rival, Duke Ephriam, disrupted slave-trade operations. With time approaching for the ships to begin their voyage, a Captain Bevins decided to form an alliance with Duke Ephriam to ambush King George and his men. Unlike many of his men, King George escaped, but those who were not massacred were loaded onto slave ships. Among those prisoners were Little Ephraim and Ancona.

Captain Bevins sailed to the French Island of Dominica, where he sold both men. An attempt to return to Old Calabar required the two men to rely on their knowledge, language, reading, writing, and negotiation skills. Their negotiating skills resulted in finding a ship captain willing to return them to Calabar, if they would stow themselves on board his ship. After they sailed to Charleston, South Carolina, and Virginia, the captain unexpectedly sold them to captain John Thompson of Williamsburg, Virginia. There, Little Ephraim and Ancona remained enslaved for five years until Thompson’s sudden death in 1772. Fortunately, little Ephraim and Ancona negotiated their return to Calabar with another ship captain.

Bristol was the captain’s first stop on his journey to Calabar. News circulated that the two Africans from Old Calabar were in port. Little Ephraim and Ancona were detained and immediately sold to a Virginia planter. Before the ship departed from the port, however, the men wrote a letter to their business partner, Thomas Jones. Eventually, Jones assisted in the release of the men.

Little Ephraim and Ancona also took their case to the King’s Bench, presided by Judge Mansfield, who determined that the men were free. While in England, Little Ephraim and Ancona formed a close relationship to Methodist clergymen John and Charles Wesley. After about two years in England, Little Ephraim and Ancona returned to Old Calabar. It is possible that they even resumed their participation in the slave trade.

Little Ephraim and Ancona’s story came to light due to the efforts of Thomas Clarkson, a British abolitionist, who traveled thousands of miles seeking testimony on the inhumanity of the slave trade. In 1790, the British House of Commons conducted an investigation of the Bristol ship captains’ actions in Calabar. The testimony provided the public insight into the cruel and brutal business of the transatlantic slave trade.