Atlantic Emancipation Celebrations

Formerly enslaved people marked the sacred moment of their freedom—whether from manumission, escape, legal abolition, or otherwise—privately and publicly. Though liberty rarely meant equality, at least not at first, individuals often referred to their new-found freedom as a turning point in their lives, evoking its arrival as a key moment that changed how they viewed themselves, their families, and their world. Many changed their names to reflect their new status and identity, adopting such surnames as Freedom, Freeland, Freeman, Liberty, or Justice, as in the case of several who found themselves free after the American Revolution.

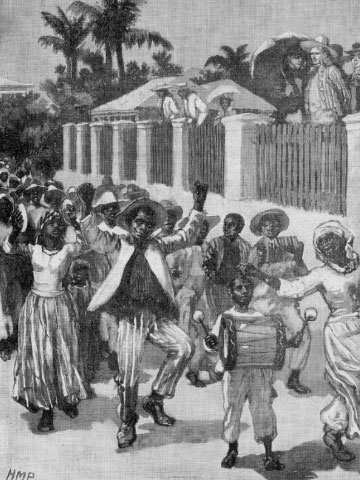

Freedpeople collectively celebrated their liberty, especially after general abolition occurred in such places as the British Caribbean (in 1834), French Caribbean (1794, then again in 1848) and the United States (in 1865). Caribbean people adapted celebrations begun in slavery, such as Jonkonnu in Jamaica and Canboulay in Trinidad (as well as various crop-over festivals resembling post-harvest holidays in pre-emancipation Louisiana). “August First” commemorations in the Caribbean marked the legal abolition of British colonial slavery on that day in 1834 but came to be celebrated outside the British colonial world, including in Haiti. In Jamaica and Trinidad, freedpeople’s commemorations of emancipation clashed with formal August First commemorations managed by British administrators and missionaries, who marked the end of legal slavery in 1834 with the beginning of a transitional four-year-long “apprenticeship” system.

In the United States, Emancipation Day and Juneteenth parades marking the legal end of slavery in North America may have emerged from an August First tradition among African-descendant communities in the broader Atlantic world—in Haiti, Jamaica, Trinidad, the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and even Liberia.

Today, emancipation celebrations, in a variety of forms, continue in African-descendant communities throughout the Americas and Europe. Such commemorations continue to inspire new cultural events, works of art, and statues and markers that are re-making public spaces in cities that once were known for their slave-ship ports and thriving slave markets.

History & Memory

Related Pages:

-

Monument to Abolition of Slavery

Monument to Abolition of Slavery

-

Toussaint Louverture

Toussaint Louverture

-

Jamaica

Jamaica

-

Monument to Abolition of Slavery

Monument to Abolition of Slavery

-

Belinda

Belinda