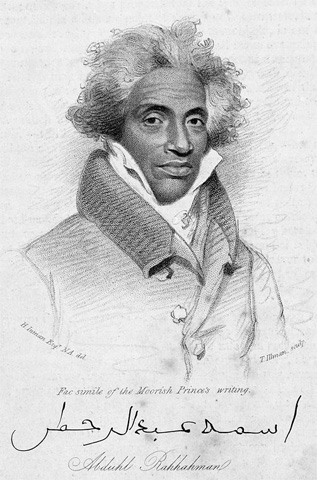

Abdul Rahman 1762 — 1829

Abdul Rahman (Abd-Al Rahman; Ibrahima abd-Al Rahman) was one of few men to return to Africa after living as a slave in the United States. His story is an extraordinary example of how some African captives were able to use limited resources and good fortune to navigate through the Atlantic world.

Ibrahima abd-Al Rahman was a Muslim member of the Fulbe people. Ibrahima was from Timbo, the capital of Futa Jalon, in what is now the Republic of Guinea on the west coast of Africa. His father was the ruler of Futa Jalon and, after studying at Timbuktu, Ibrahima became a colonel in his father’s army. In 1788, when Ibrahima was approximately 26 years old, he was sent by his father on a campaign to subdue a rival nation that had interrupted Timbo’s coastal trade. As Ibrahima returned from the successful campaign, he and his men were ambushed. Caught in a failing retreat, Abdul Rahman and a small cadre of troops fought unsuccessfully to gain the upper hand. They put up a final defiant stand that ended in defeat: Abdul Rahman and fifty of his men were sold to a British slave ship captain.

Ibrahima arrived in one of the major gateways of the transatlantic slave trade, the French island of Dominica. From there he was carried to New Orleans, Louisiana and then Natchez, Mississippi where he was sold to Colonel Thomas Foster, a plantation owner. It was there that Ibrahima spent the next forty years of his life as a field hand and foreman.

He claimed to have converted to Christianity when he married his wife Isabella, another of Foster’s slaves. Together they had five sons and four daughters. Ibrahima’s fortunes changed one day while selling produce in the Natchez market, when he was reacquainted with an old friend, Dr. Coates Cox. Ibrahima and his father had aided Dr. Cox during his travels in Africa. Dr. Cox tried to purchase Ibrahima from Thomas Foster, but he refused the offer. Two decades later, Dr. Cox’s son, with the assistance of Andrew Marschalk, a local newspaper publisher, launched a campaign to liberate Ibrahima.

In 1826, Ibrahima wrote a letter in Arabic to his family. Marschalk forwarded the letter to other politicians until it reached the U. S. Consulate in Morocco. The Arabic handwriting caused others to believe that Ibrahima was a North African Moor, not an African Muslim. The Sultan of Morocco requested that President John Quincy Adams and Secretary of State, Henry Clay arrange Ibrahima’s release in 1829.

The campaign successfully brought Ibrahima’s plight to the attention of Secretary of State Henry Clay, who convinced President Adams to free Ibrahima. Marschalk, who erroneously believed that Ibrahima was from Morocco, sent a letter, which he believed to be evidence of Abdul’s claims to the high rank of Sultan. The letter actually contained scriptures from the Qur’an which Ibrahima memorized and wrote down. Despite these mistakes, the Sultan of Morocco was convinced and offered the American consul funds to liberate Ibrahima and pay for his passage to Africa. In 1828, the Adams Administration gave Marschalk permission to secure Ibrahima’s freedom.

Although freed, Ibrahima abd-Al Rahman was not satisfied until his wife and children were also free. From residents of Natchez, Ibrahima collected funds to liberate Isabella. They then traveled throughout the North meeting with abolitionist groups and others to raise the money necessary to purchase their children from Foster. During these travels, Ibrahima relayed his testimony to Rev. Thomas H. Gallaudet who published it as A Statement with Regard to the Moorish Prince, Abduhl Rahhahman. The pamphlet circulated but did not raise sufficient funds to liberate Ibrahima’s entire family. However, he was able to liberate two of his children and their families, before they immigrated to Africa.

In 1820, the colony of Liberia was established in West Africa for the relocation of free blacks from the United States. The American Colonization Society and other religious organizations provided funding to establish the settlement. Instead of returning to his original community of the Fulbe people, Ibrahima and his family were sent to Liberia. Unfortunately, shortly after his arrival Ibrahima died on July 6, 1829, at the age of sixty-seven.

Ibrahima abd-Al Rahman’s life, though tragic toward its end, was a remarkable journey. The avenues he and others took to acquire freedom was exceptional. His legacy has been celebrated in an autobiography and film entitled Prince Among Slaves.