Mary Perth 1740 — after 1813

Mary Perth arrived in Freetown, Sierra Leone, in search of freedom and self-government after she left behind slavery in the Unites States and discrimination in Nova Scotia (Canada). Mary was one of thousands of other black settlers whose dreams of self-determination did not materialize in Freetown in their lifetime.

Yet, Mary’s life would have been very different if she had remained in the United States or Nova Scotia. In Freetown, Mary Perth was able to operate a business and vote, a privilege not extended to women in the United States until 1920. In Freetown’s legal system, Mary had the right to be judged by a jury of her peers, unlike her counterparts in North America. In addition, interracial marriages were legal, centuries before the United States Supreme Court declared such marriages legal in the mid-twentieth century. Little did Mary know that her quest for freedom and equality would take her to four countries and three continents over the course of her lifetime.

Born in 1740, Mary was enslaved by John Willoughby of Norfolk, Virginia. Willoughby’s wife gave Mary a copy of the New Testament. It is unknown how or when Mary learned to read, but it is possible that she read the New Testament to her fellow slaves during secret meetings in her Norfolk neighborhood.

In 1775, the thirteen North American colonies were on the verge of a war for independence from Britain. Virginia Governor Lord Dunmore ordered martial law and issued a proclamation offering freedom to those slaves willing to join the British cause—but only if their masters were rebels (American patriots). The Willoughbys were Tories, loyal to the British, therefore the offer of freedom to slaves did not apply to Mary and her daughter, Patience.

In early 1776, American forces mounted an attack on the British position in Norfolk. As Dunmore’s naval fleet began to retreat from the city, the Willoughby family and their slaves sought refuge aboard British ships. Dunmore’s naval fleet retreated north to Gwynn’s Island, where a severe smallpox epidemic spread throughout the encampment. After quarantine, Mary and Patience survived the scourge. The American Patriots’ relentless bombardment of the British encampment forced Dunmore’s naval fleet to retreat from Virginia and sail north to New York in the spring of 1776.

In New York, even though Mary was separated from the Willoughby family during the chaos of war, she legally remained a slave. For several years, Mary lived on Manhattan Island where she likely worked as a domestic laborer for the British Army. There she met and married Caesar Perth, who was from Norfolk, Virginia.

News arrived in New York in 1781 that the British surrendered in Yorktown, effectively ending the war. This event caused the Perth family to confront two new crises. The first crisis was the terms of the peace treaty; the British agreed to return fugitive slaves to the victorious Americans. The Perth family’s fears were relieved when British General Guy Carlton declared that all of the blacks who had joined the British before 1782 would be freed. The second crisis centered on the fact that Mary needed to find a means to evacuate New York before she was discovered by the Willoughby family or the authorities. Mary and Caesar were able to acquire certificates of freedom, which effectively served as passports to the northern British territory of Nova Scotia.

For the first time in their lives, they were legally free. On July 31, 1783, when the Perth family boarded the ship L’Abondance, Mary was pregnant with her second child, Susan. They arrived in Nova Scotia and settled in Birchtown.

Building a settlement in Birchtown meant confronting numerous obstacles. Acclimating to the blistering cold northern climate and finding land useful for farming was a challenge. The Perth family escaped neither discrimination nor the practice of slavery. Some of the white Tories brought their slaves with them to Nova Scotia. A hostile reception from the white population and government officials delayed or denied promises of land grants to black immigrants. Shortage of work and land created economic hardships and opportunities for white Nova Scotians to exploit the labor of the black immigrants.

Disappointed by broken promises and the hardships of life in Nova Scotia, the Perth family was attracted to another opportunity to seek a promised land. Representatives from the Sierra Leone Company promised a better life, land, education, self-government, equality with whites, and Christian missions in Africa. In January 1792, the Perth family and hundreds of others boarded the Sierra Leone Company fleet of ships as they sailed across the Atlantic to the settlement of Freetown, Sierra Leone, West Africa.

When the settlers arrived in March, they discovered the promise of a new settlement included risks. Enduring the dry and rainy seasons and suspicious reception of the indigenous African people was a challenge for the Nova Scotian settlers. On arrival, they were surprised to discover that the Sierra Leone Company’s board members reneged on many of their promises, including self-government. Preachers and others in leadership within the black community protested and petitioned the Sierra Leone Company to fulfill its original promises.

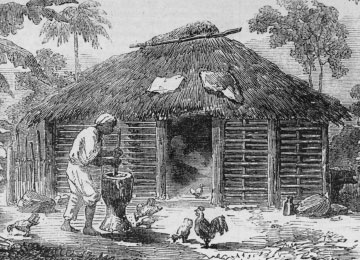

When land was allocated to the settlers, Caesar Perth built a two-story house and farm on Waters Street. Unfortunately, after establishing a home for his family, Caesar died. Saddened by the loss of her husband, Mary sold the farm and converted her home into a boarding house for travelers arriving in Freetown.

Without warning in 1794, a French fleet attacked and raided Freetown, forcing many settlers to take flight. After the French departed, the governor recognized Mary’s loyalty and heroic acts during the crisis. The governor offered Mary a paid position as the governor’s housekeeper, which required her to care for and teach African-born children in the governor’s residence. Later, Mary accepted the governor’s offer to travel with him to London as his housekeeper. Susan died in England, and six years after arriving in London, Mary returned to Nova Scotia alone. Mary Perth likely died after 1813.