African Diaspora Culture

Africans brought to the Americas the greatly varied cultures of their homelands, including folklore, language, music, and foodways. In forging new lives with one another, as well as neighboring Europeans and Native Americans, rich varieties of African diaspora culture took root in a New World decidedly shaped by the cultural innovations of Africans and their descendants.

Folklore

Survivors of the Middle Passage gave new life to certain African themes, characters, and stories in their homes and neighborhoods in the New World, and much of the folklore of the African diaspora reflects a dynamic combination of African traditions and New World influences. Folklore often conveyed religious worldviews and beliefs while relating the more mundane routines of everyday life-from the way families functioned through the rituals of birth and death, to simple routines of cooking and clothing, and the local calendar of celebrations.

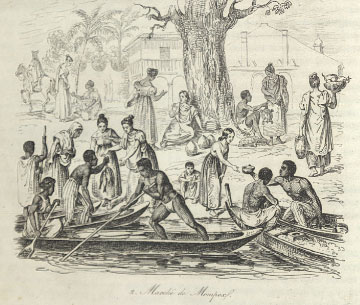

A range of artifacts manufactured by enslaved craftsmen and women with local materials helped to transmit folklore through such objects as canoes, trays, combs, stools and ceramics shaped for daily use. Some of those crafts and skills, and the objects themselves, survive to this day. At every turn, folklore of Africans and their descendants in the Americas was crucially fashioned not simply by an African past, but by the complex ways African cultures interacted with European and American peoples and cultures in the New World.

This was, perhaps, most obvious in language. Phrases, words, and patterns of speech, lived on from African vernacular. In time, however, descendants of African slaves came to speak the local variants of English, French, Spanish, Portuguese, and Dutch. Similarly, the folklore which evolved, normally in the adopted language of the Americas, was itself shaped by contact with other, non-African peoples of the Americas. The rich world of folktales—from Bre’r Rabbit and the Uncle Remus stories of the U.S. South (with their links to Native American and African folklore), to the Anansi tales of Jamaica, and the bouki stories of Haiti—all used local imagery to make their point. Such examples evolved as a folklore which spoke not only to the world of slavery, but offered lessons for daily life and survival in the harsh conditions of bondage.

Language

Africans forced onto slave ships were drawn from a large range of societies and cultures. Though Europeans tended to describe them simply as “Africans” (a term which no African would have recognized), African individuals viewed themselves according to kinship groups, lineage, and ethnicity, defined by distinct traditions and languages. In this way, those belonging to distinct groups, lineages, and ethnicities tended to view others as “foreigners.” The language of race was introduced by Europeans beginning in the fifteenth century.

For the enslaved, understanding the language of European and American slave traders and plantation owners was necessary to understand the new world of Atlantic slavery that legally determined so many aspects of their lives from life to death. A new “pidgin” language evolved, first developed from the language used by early Portuguese sailors and African traders along the West and Central African coast. As more Europeans arrived, and as their trading presence became more concentrated, a similar pattern evolved for all the major European languages.

In addition, bi-racial children born on the coast to African women and European sailors or traders were often fluent in both languages and were employed as interpreters and traders. At the points of African embarkation on slave ships, and then in the Americas, African and European people worked as interpreters, using a mix of African and European languages in order to convey instructions.

In the Americas, new languages emerged and evolved. They were, again, pidgin or creole languages which emerged from the blending of African, European, and Americanized-European languages. Eventually, forms of pidgin, differing from colony to colony, emerged into fully-fledged creole languages of their own. All bore strong linguistic features of the dominant African group in the region. American-born slaves grew up speaking these languages naturally. A similar pattern happened among Europeans and their American-born offspring. Thus, white and African North Americans spoke differently from their European and African forebears. Europeans and Africans across the Americas in Cuba, Brazil, Suriname, or Martinique, for example, spoke with distinct local voices—accents, vocabularies, and intonations.

Music

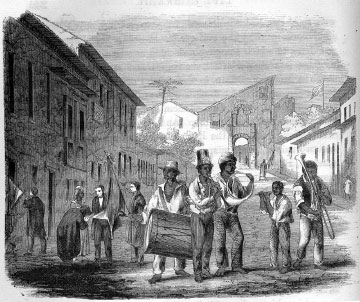

European slavers deprived African captives of material possessions during the Middle Passage, but survivors throughout the Americas re-created variants of familiar instruments, if possible. When resources were not available, they created new instruments. Materials found in diverse environments throughout the Americas varied from gourds, sea shells, wood, bones, and string. On their own time, enslaved people used available materials to construct musical instruments, such as drums, rattles, bells, banjars (an ancestor to the banjo), fiddles, and other instruments. In the process, enslaved musicians created new forms of musical expression that informed social and religious life in the Americas.

Throughout the Atlantic, Africans and their descendants created distinctive forms of musical expression, depending perhaps on the most dominant or influential African ethnic group in their communities. Other factors included European and Native American peoples’ culture and religion. Numerous factors influenced how African, European, Native American musical traditions synchronized into new forms of music throughout the Americas. However, music in maroon communities and other isolated regions created the best possible conditions for the persistence of African cultural forms, whose meanings were adapted to New World conditions.

Fearing the use of loud instruments to communicate rebellions, Europeans created laws in the Americas to prohibit large numbers of enslaved people from gathering on their own time for funerals or other events. They also feared other features of African expression, such as drumming and calls on conch shells. Despite attempts to eliminate communication, enslaved communities throughout the Americas found means to communicate through song and music by using hidden codes in the words or meanings of their songs.

African and European cultures influenced each other in different ways throughout the Americas. From the sixteenth to eigtheenth centuries, in many places in Brazil and the Caribbean, Whites were but a small minority of the population, and their culture and lifeways were heavily influenced by those of the enslaved black majority. In British North America, enslaved people infused their musical culture with European instruments, songs, and dances, creating new forms of expression that incorporated and adapted elements of multiple cultural traditions.

Throughout the Americas, the enlistment of Africans and their descendants in the military also exposed blacks to European drums and wind instruments like trumpets, fifes, and horns. Groups in the Caribbean and the southern United States, such as the Tuk Band of Barbados, are legacies of those traditions.

The sacred music of Protestant and Catholic Christian religions profoundly influenced the instrumentation and songs of the African diaspora over the decades and throughout the Americas. Some enslaved people converted to Christianity while others rejected it as the religion of their oppressors. Those who attended church learned and reinterpreted western hymnal and choral singing for their communities. In some cases, enslaved people continued to use elements of African music in their religious expressions, including syncopation, polyrhythms, and call-and-response. In the United States, nineteenth-century enslaved people also combined dance, music, and Christian hymns in the “ring shout,” as a distinct form of religious worship. Elsewhere, as with maroons in Brazilian quilombos, combined dance, song, instruments, and martial arts in Capoeira, a form of self-defense disgused as a dance.

Christian holidays and festivals were another occasion for European and African cultures to merge and influence one another. Christmas traditions of John Canoe, or “Jonkanoo,” took different forms in African diaspora communities in the Caribbean, Bahamas, and southern United States. Enslaved peoples’ participation in Carnival in Brazil and various Caribbean societies provide other examples of cultural blending and regional variation.

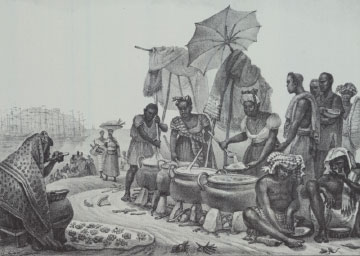

Foodways

Africans survived on the slave ships on diets which the European captain thought were appropriate for their survival. It was a crude mix of foods acquired on the African coast, imported on the ship, and prepared on board. Eating took place in the cramped and generally squalid circumstance of the ship and in conditions which often helped the spread of sickness among the African captives. Oats, peas, beans, biscuits, maize, plantains, and rice were boiled and mixed with oil and perhaps some pepper. The ship captain’s plan was to provide foods with which Africans were familiar. Survival of the captives required the crew to carry a plentiful supply of fresh water. In order to survive several weeks at sea, the ship often used more space to carry water barrels than captives. Major disasters, and huge loss of life, sometimes occurred on slave ships because of water shortages.

In the Americas, foodstuffs from Africa such as rice, ackee, and yams, as well as imported foods from Europe and other parts of the Americas became a basic diet for enslaved communities in the African diaspora. Salt fish from Newfoundland fisheries was provided on Caribbean plantations. With these basics, enslaved people developed their own distinctive foodways.

Slave owners rationed food to their slaves. Some enslaved people fished, hunted wild animals, and grew crops in gardens allotted to them by their owners. Some domestic slaves ate food similar to their owners. In large part, enslaved people’s diets depended on the culture and policies of their owners. When a slave owner fell on hard economic times, their food rations were diminished. Some owners allowed their enslaved people to roam, in order to scavenge for food, in times of drought or crop failures. When times were good for the owner and supplies were plentiful, extra rations might be granted to enslaved laborers on select occasions, such as on holidays, as incentives for increased production.

As with languages and religions, the foodways which enslaved people in the New World developed were blends of African, European, and Native American foodstuffs, spices, ingredients, and cooking methods. There emerged a distinct blend of Africa and the Americas. The use of particular ingredients, ways of cooking, and the melding of various African habits with the patterns and ingredients available in the Americas all created distinct patterns of slave diet and cuisine. For example, in Jamaica, Ackee and salt fish—today a national dish—derives from the fruit, ackee, native to West Africa, and salt fish, from the teeming fishing grounds of the Newfoundland banks, initially given to enslaved people by their masters. And all garnished with local spices. This national dish, a mix of ingredients from Africa and the Americas, was created by people who blended their foods—local and imported—as best they could from what was available. It established itself as a palatable and tasty staple of local culinary culture.